The Five Most Potent Small-Block Chevys Of the 1960s

When you think of the 1960s, and the powerplants that urged the cars and trucks of those days onward, what’s the first one you think of? Of course… the Chevrolet small-block V-8 (SBC), in production since 1955, and by the time 1960 rolled in, was cruising up and down the Main Streets of the USA in gracefully-styled Bodies by Fisher.

By then, it had earned a reputation as a go-to engine for hot rodders, race-car builders, and customizers. Not just because of the ready supply of them, but also because of the advances that Ed Cole and his team of Chevrolet engineers made sure were in that engine from the get-go, including a “thinwall” cast iron block and cylinder heads that weighed less than the old “Stovebolt Six’s” block and head did; lightweight stamped steel rocker arms and hollow pushrods to help oil the engine’s top end while shedding weight, all in a compact package that could–and did–fit in just about anything.

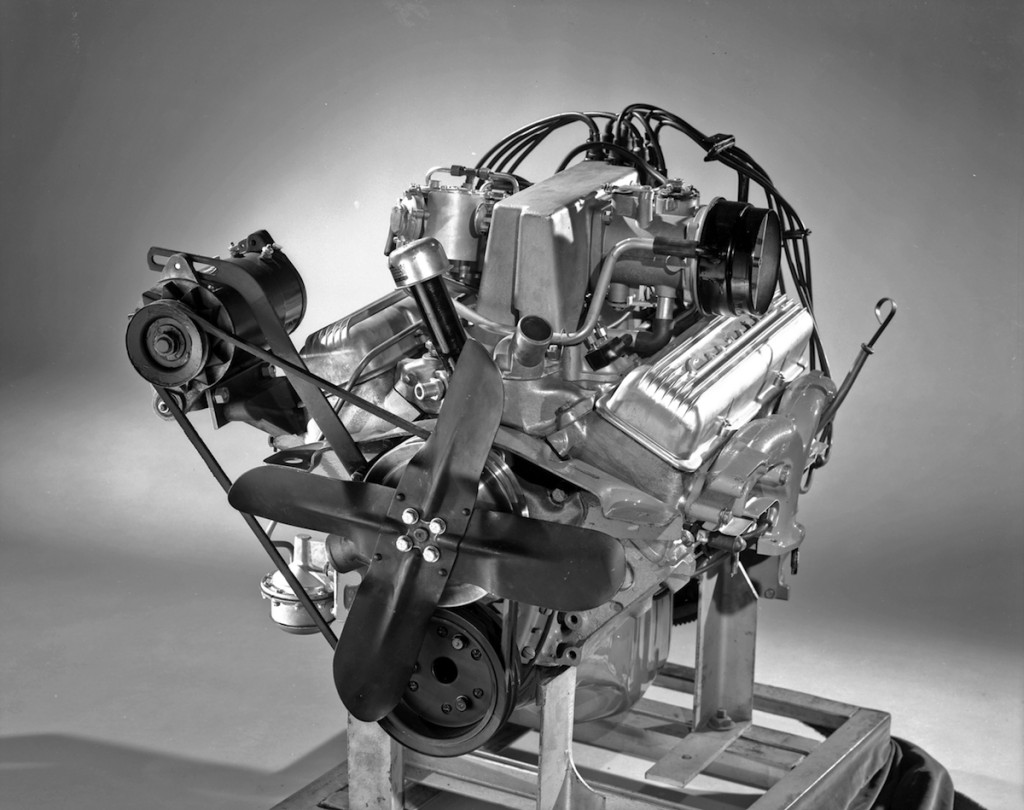

Chevrolet didn’t rest on its laurels after the smallblock debuted in 1955. Spurred on by an internal memorandum that Zora Arkus-Duntov wrote to his bosses soon after joining Chevrolet Engineering in 1953 (“Some Thoughts About Youth, Hot-Rodding and Chevrolet”), they developed high-performance parts like the “30/30” camshaft, 2×4-barrel carburetor intake systems and mechanical fuel injection, while the aftermarket–spurred on by early-production smallblocks shipped to the shops of Vic Edelbrock and others–offered a huge selection of go-fast parts like 3×2-barrel carbs and manifolds; exhaust headers; high-compression pistons; supercharger set-ups, and lots more.

With all that in mind, here are the five most potent smallblock Chevrolet V-8s from the 1960s:

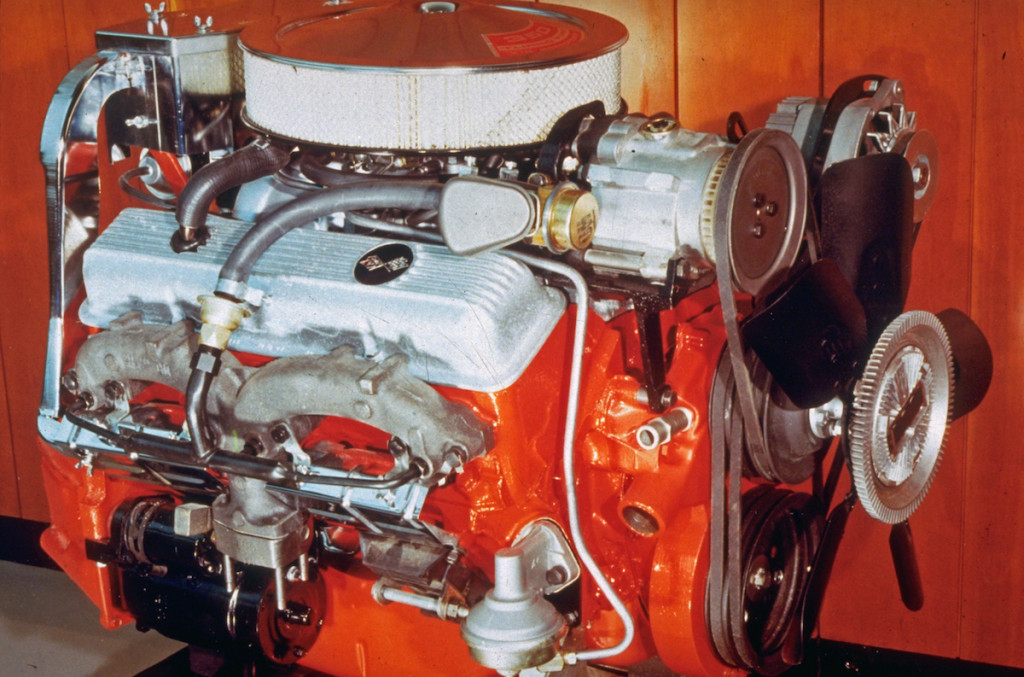

-283 (1960-1967): Before the displacement boost in 1957 from 265 cubic inches, the smallblock had received its first group of high-performance parts like the “30/30” (or “Duntov”) camshaft, and dual-quad carburetors and intake, that were not only available as over-the-counter items from Chevrolet Parts, but were also offered as factory-installed SROs–Special Racing Options–on the 1956 Corvette.

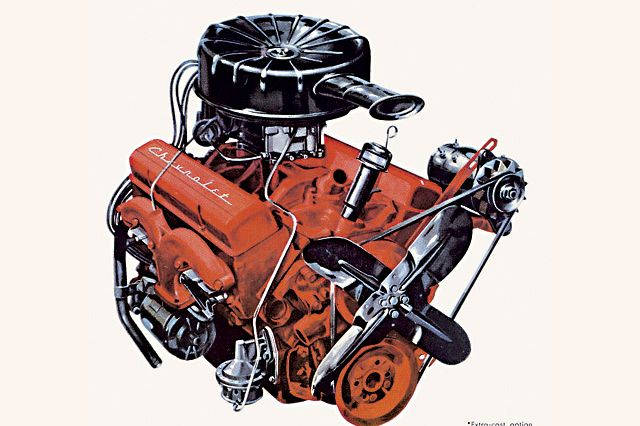

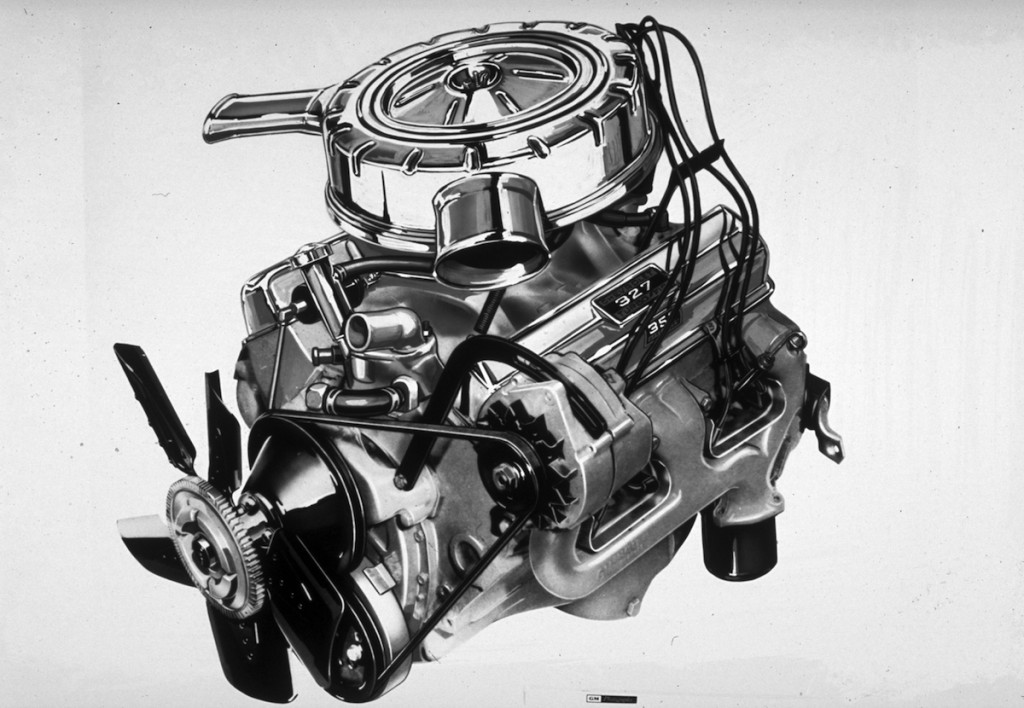

For 1962, the small-block’s displacement grew from 283 ci., to 327 cubic inches–and this was the scene that greeted Chevy lovers when they popped the hood of a 327-powered BelAir that year. (Courtesy Chevrolet/GM Media Archives)

By 1960, Corvette’s option list included no fewer than four high-performance 283s: the RPO (regular production option) 469 and 469C dual-quad versions, the difference being the “C” version had a solid-lifter cam that bumped its factory horsepower rating from 245 to 270; and the RPO 579 and 579D fuel injected 283s, with the solid-lifter “D” version putting out 290 horsepower to the hydraulic-lifter 579’s 250 horsepower.

Chevrolet’s 1960 plans also included fuelies with aluminum heads, with horsepower ratings of 275 (with a hydraulic-lifter cam) and 315 hp (with a solid-lifter cam). Unfortunately, casting problems with the high-silicon aluminum alloy that Chevy’s engineers chose kept those heads from ever reaching production, and the few sets that were made wound up in the hands–and Corvettes–of Briggs Cunningham’s race team that ran at the 24 Hours of LeMans.

The production high-performance smallblocks–and the 230 hp four-barrel version–carried over to 1961, which was the 283’s last hurrah as a factory performance engine. Changes in the works for 1962 relegated the 283 to two-barrel, regular-gas, standard-engine duty, where it became America’s Great Grocery Getter–saving its owners money at the pump, so they could pump more groceries for their growing families into the back of their Bel-Airs, Biscaynes and Impalas.

Thanks to Zora Arkus-Duntov’s foresight, one of the first production Chevy small-block V-8s was shipped to Vic Edelbrock’s shop right from the Flint (MI) Engine Plant in 1954. Here’s VIc Sr. at the dyno, with a smallblock wearing Edelbrock’s six-carb intake and finned chrime valve covers. (Courtesy Edelbrock)

1967 was the last year of production for the 283, though its block lived on in the 307 through 1973.

-327 (1962-1969): If there’s a Chevy engine that Bowtie lovers associate most with the 1960s, its the 327. Why? because it was factory-installed in every Chevrolet car line of the decade, except for the Corvair (a condition that aftermarket conversion kits later addressed).

1962 saw the smallblock not only get bored out to 4 inches–something that machinists and engine builders across the land had discovered was possible, as had Chevy’s engineers–but its stroke was lengthened from 3 to to 3 1/4 inches That added up to an engine that produced the low-end torque to get a “Jet-Smooth” Impala moving effortlessly, but also resulted in a high-revving screamer when the right combination of parts was built into it.

And engine builders had a great starting place–the 327’s block, the latest upgrade to the classic smallblock design which came from the factory with either two-bolt or four-bolt main-bearing caps, depending on the factory power rating and intended service. (In coming years, that set off one of the great treasure hunts of all time–looking for four-bolt main 327 blocks in salvage yards from coast to coast.)

Those salvage scroungers also looked out for the new-for-1962 “double hump” heads, so called because of a casting symbol on one end of the head casting that denoted 2.02-inch-diameter intake valves, the largest size used on a factory-built smallblock. (And you know what results when you flow more air into an engine.)

In carbureted form, the 283-inch Chevrolet small-block V8 was good for up to 270 horsepower; with a solid-lifter cam and Rochester mechanical fuel injection (seen here), the factory horsepower number grew to 290. (Photo courtesy Chevrolet/GM Media Archives)

The 327 wasn’t just an engine–it was a legend, in the hands of builders, tuners and racers alike. Two versions of it merit inclusion on this list, starting with:

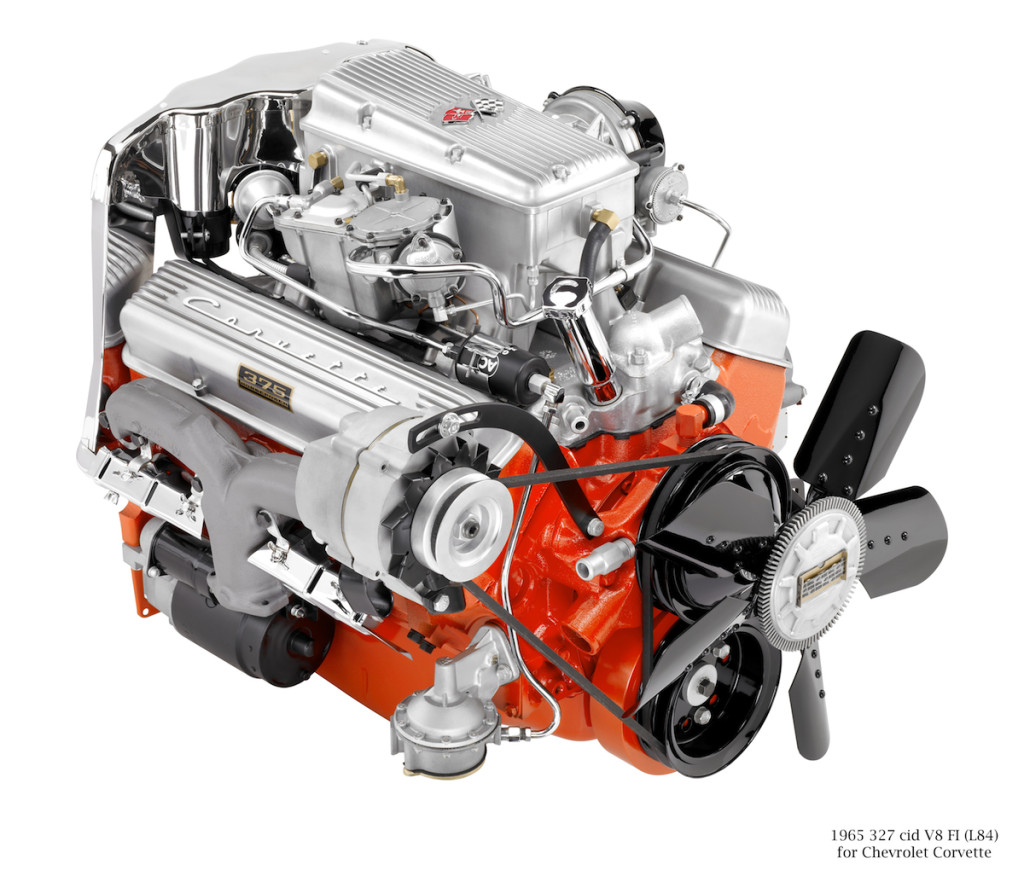

-RPO L84 fuel injected 327, 360 and 275 Horsepower: L84 was the option code you had your Chevy dealer put on the order blank if you wanted the updated version of the small-block sporting Rochester mechanical fuel injection, a late-1957 addition to the Corvette’s option list and a mainstay of America’s Only True Sports Car well into the Vette’s second generation.

The displacement boost to 327, and other upgrades for ’62 such as “double hump” heads and a compression ratio bump from 11.0:1 to 11.25:1, added the extra power over the the ’61 fuelie. Then, for ’64, factory horsepower got bumped up to 375.

Year-after-year updates and improvements to the fuelie smallblock grew its factory horsepower rating to 375 in 1965, its last year of production. (Courtesy Chevrolet/GM Media Archive)

There it stayed for 1965, when the first 396-inch Mark IV big blocks joined the Corvette option listin the spring of that year. Thanks to the 396’s $292.70 sticker price versus the fuelie’s $538.00 tariff, the fuelie’s days were numbered, and it went away after ‘65.

But that didn’t keep engine builders, racers and–in later years–restorers from seeking them out for their projects. But, if they wanted the ultimate in carbureted 327 power, they looked for…

-RPO L79 327, 350 Horsepower: To create this engine, Chevy’s engineers took the best parts they’d come up with for the smallblock, topped it with a four-barrel Holley under a chrome twin-snorkel air cleaner, and turned it over to the production crew who installed it in ‘glass and steel bodied Chevys, large and small.

In a Chevelle, it was a great performer, one that could give a 389-cubic-inch Pontiac GTO a run for its–and its owner’s–money. In a much-lighter ChevyII, it was a giant-killer, setting track records in Stock classes at dragstrips from coast to coast while showing big-block-powered cars its back bumper.

Chevy’s “Giant Killer”: the 350 horsepower RPO L79 327, which graced the options list of Corvette, Chevelle and Chevy II from 1965-67.

When it came for “Top Stock Eliminator” to be run at the NHRA and AHRA national events and other big race meets, where the two quickest Stock class winners would face off for a big prize whose bragging rights were as big as the trophy or cash payout that came with it, many a time it was the screaming small-block Chevy that lit the win light over its larger-engined, but heavier, competition.

On the street, it was the ultimate sleeper. There was no special “L79” identification outside, just the same fender badge that all 327s got. Atop the valve covers were understated “350 horsepower” stickers. But, once you turned the key, put it in gear and got on it, you had a car that could easily embarrass just about any factory musclecar of the time. (Especially the Blue Oval variety!)

-RPO Z28: For this smallblock, you have to thank Vince Piggins, a veteran race-car builder who’d headed up Chevy’s racing skunkworks. After heading up the Hudson factory program that created the “Twin H-Power” Fabulous Hudson Hornets that ruled on the dirt ovals of NASCAR’s early years, Piggins moved to the South East Development Company (SEDCO), which turned low-line ’57 Chevy 150 business coupes into the “Black Widows” that gave the supercharged Fords and Mercurys more than they could handle.

After NASCAR banned blowers and fuelies, Piggins moved to the GM Tech Center, where his “Chevrolet Product Promotion Engineering” department gave clandestine (‘back door”) support to Chevy racers, skirting the company’s no-racing edict. So it was in 1966, with the debut of the all-new Camaro that September, and SCCA’s Trans-American Sedan Championship series in its first year, with you-know-whats stampeding to the winner’s circle in that series’ big-engine class time after time.

The 283 crank and rods, stuffed into a 327 block made for the high-revving 302 ci. Z/28. Avaialble from ’67-69, it was top contender on the Trans-Am racing circuit. An optional Cross-Ram intake with dual 4-bbl. carburetors was available for 1969. This is a very fine example of one. Image: Detroit 60

Piggins saw that Camaro was a natural for that series–not just to compete in it, but to own it. So, he went through the factory parts bin to find the powertrain and chassis items from other Chevys that would bolt right on to the new F-Body. That included an engine with a displacement meeting SCCA’s 5-liter (305.5 cubic inch) limit. Swap in a forged 3-inch stroke crank and rods–originally from the 283–into the L79, and voila–a 302 cubic inch high performance small-block!

This is the very ’68 Camaro Z/28 convertible Pete Estes drove during his tenure as the President of the Chevrolet Division. It served as a test/development vehicle. No, there were any actual production Z/28s produced, but when you’re the big cheese at GM, you can have pretty much anything you want – at least back in those days. This particular car was also used as the test vehicle for cowl induction and the Cross-Ram intake system that debuted for ’69.

Piggins installed one of them, plus the heavy-duty parts he’d researched, into a prototype Camaro, and then–according to legend–pulled off one of the greatest car swaps in Chevy history. Per the legend, Dollie Cole–wife of Chevy’s now -General Manager, Ed Cole- had a new Camaro SS/RS convertible that was in the executive garage for its first oil change and service. Piggins took his prototype to the executive garage, and had the crew there inform Mr. Cole that his wife’s car would be ready first thing in the morning, and Mr. Piggins had brought over a car he could drive home and bring back the next day.

Ed Cole drove the prototype home, and the next day, summoned Piggins for a lunch meeting at the best restaurant in Detroit–the Executive Dining Room on the 14th Floor of the General Motors Building. Not only did Piggins make the lunch date, but he came armed with a “build book” that not only detailed the items that Product Promotion Engineering installed on the prototype Camaro that Cole drive–and enjoyed–but also listed those items‘ costs. As nearly all of them were already in production, tooling and other get-ready-for-production costs were near zero–something any GM Division’s General Manager could appreciate, even if he wasn’t the “product guy” that Ed Cole was.

After lunch, Cole–according to the story–then prepared and sent out the authorizing memorandum announcing the Camaro Special Performance Package and its contents, which then received the factory RPO code of Z28. Do we need to tell you what happened next?

LT-1: Another Off The Shelf Special: We said “five” small-blocks – but, in the spirit of Chevrolet back then–combining engineering, style and value like no other low-priced car maker – we’ll give you a sixth small-block screamer: The LT-1. It combined the best of the 327s and 283s before it with the engineering advances that grew the smallblock from 327 to 350 cubic inches.

And, in prototype form, it was put together by none other than engineer-turned-racer Mark Donohue, at the Penske Racing shops then located near Philadelphia in Newtown Square, Pennsylvania (which, by the way, were just south of Bill “Grumpy” Jenkins’ shop in Berwyn).

Open-element air cleaners were a giveaway that the engine beneath it was no mere grocery-getter. The aforementioned ’67-69 Z/28’s 302-inch smallblock wore one, as did the LT-1 that succeeded it in the Z-28 for 1970, which was also a Corvette option from 1970-72. . (Courtesy Chevrolet/GM Media Archives)

Here’s what his co-conspirators, Car and Driver Magazine, said about that engine, which went into the “Blue Maxi” project Camaro which graced their September, 1969 cover:

“The engine is next year’s incarnation of a Z/28, the LT-1, a stroker 302 with 0.48 inches more arm. It was actually converted from a 350 cubic inch/350-hp Corvette, vintage 1969. The conversion included the solid-lifter Z/28 camshaft, Z/28 intake manifold and carburetor, and 800 cubic-feet-per-minute Holley 4-barrel. Forged 11.0-to-one compression pistons and 4-bolt main bearing caps are a standard part of the package. The result is a 370-hp Z/29 engine compared to the 290 hp of the original 302 unit in the Z/28.

“It is true that some modifications were made—why else Roger Penske? If there is a pipeline from Chevrolet Engineering, and Chevrolet would deny that in extremis, it must make at least a short stop in Philadelphia (Newtown Square in nearby Delaware County, actually–Scott) on its way to Midland, Texas. Initial problems with the carburetion were solved by quiet recalibration by Sam Eckerd, and it would come as no surprise if it were done with the help of coded messages from the factory.

“Basically, it was just re-jetted with some additional help in the off-idle transfer system. The timing was also advanced a bit. The result is a transformation of the engine.”

And that transformation made it into production Corvettes and second-generation Camaros–but didn’t reach the dealers until late February of 1970. That’s because of two decisions that John DeLorean, who became Chevy’s General Manager early in 1969, had to make thanks to two big production hold-ups. One was a strike at Chevy’s St. Louis Assembly plant, where Corvette production had been shut down for four months. DeLorean ordered the ’69 model run extended four months into the fall to fill the unbuilt orders for 1969 Corvettes they had, with the 1970 Corvette to go on sale after New Year’s. The other was the tooling foul-up involving the second-Gen F-Body’s rear quarters, which led to a massive stamping die re-design which pushed back the start of 1970 Camaro and Firebird production six months beyond its summer ’69 target date.

No strike at St. Louis and no tooling problems with the second-gen F-Body–and the LT-1 would have been in the Chevy showrooms in September of 1969. Even then, the Corvette version would have carried the 370 horsepower rating while the Camaro version was rated at 360, because of its factory air cleaner, so sayeth Chevrolet back then.

Those smallblock screamers not only won races and set track records, but they also became legends and must-have engines for builders and restorers alike.

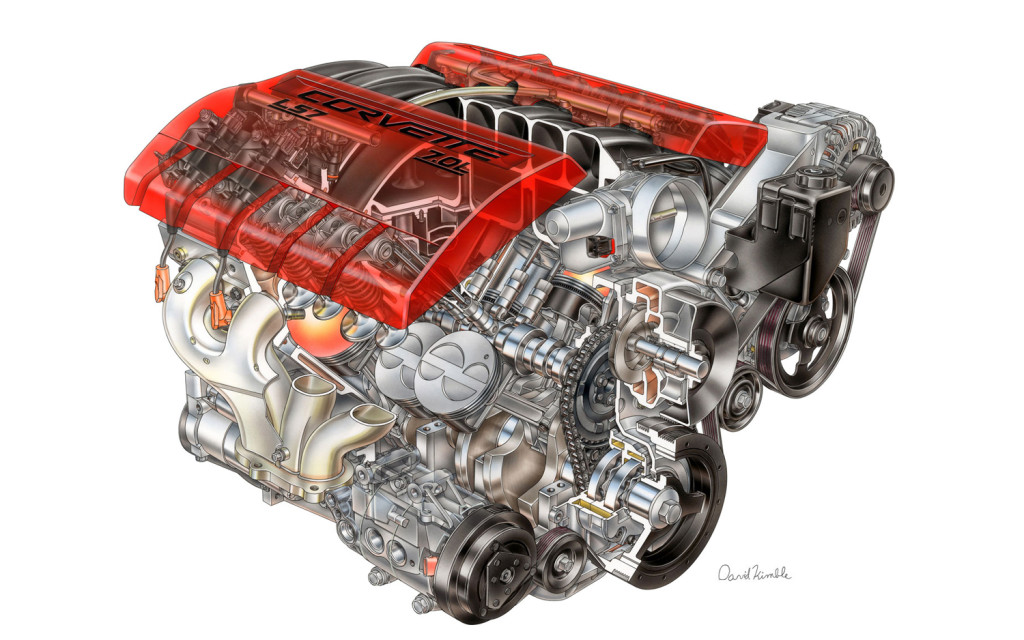

They were also the inspiration for the generations of Chevrolet high performance engines to follow, from the “ZZ” crate engines to the “LS” engine series to today’s LT powerplants!

Scott brings his extensive background of automotive journalism to Timeless Muscle Magazine. Having staffed for many well-noted print and digital classic musclecar magazines, as well as authoring several how-to manuals, he’s the real deal.